While some cities trace their origins to ancient Rome, Edinburgh owes its cultural identity more to Scotland’s intellect than military might. Often deemed the “Athens of the North”, this capital has long been a hub of philosophy and learning in the same spirit as Greece.

Nowhere is this legacy clearer than on Calton Hill, where a colossal statue of Greece’s pioneering thinker Aristotle stands tall. His presence represents the triumphs of reasoning and enlightened thought that Scotland came to champion through influential figures like David Hume and Adam Smith.

This tradition can be traced back to Alexander the Great, whose ferocity on the battlefield was matched only by his brilliant military tactics. Legend tells how even the wildest of horses, Buscephalas, was tamed by Alexander’s cunning wits rather than brute force alone. For Scots, this epitomizes their belief that ideas can conquer all.

Though small in size, Scotland’s impact on the world through cultural and intellectual exports has been hugely disproportionate. Even towering over Calton Hill, the unfinished National Monument stands as a symbol of grand ambitions achieved through the power of imagination and ingenuity rather than brawn alone.

So while other cities celebrate empires built on dominion, Edinburgh takes pride in the thinkers, artists and innovators who have advanced society through alternative means. The spirit of creativity, discovery and progressive thinking that defined the Scottish Enlightenment still permeates these streets to this day.

The Curious Case of the Edinburgh Market Cross

As I approach the historic market cross in the heart of Edinburgh, I can’t help but be struck by its curious nature. This little turret, which one must navigate around to reach it, stands as a relic of a bygone era. Once the focal point of the city’s bustling marketplace, it now seems almost out of place amidst the modern shops and pedestrians.

In days of old, this was where criminals would be punished, their ears nailed to the cross as a public spectacle. Hardly a pleasant way to spend one’s day, but it served as a stark warning to would-be wrongdoers. More importantly, however, the market cross was a hub of information dissemination. As shoppers went about their business, they would receive the latest news and announcements shouted from the top of the structure by town criers.

This tradition, though now largely symbolic, persists to this day. Even in the modern age, when news travels at the speed of the internet, Edinburgh clings steadfastly to its historical customs. Just three days after the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, a man dutifully climbed atop the market cross to inform the public of the monarch’s death. Similarly, when King Charles III was crowned, another individual made the ascent to declare the new sovereign’s accession to the throne.

The reasoning behind these delayed proclamations is equally curious.

Apparently, it was once necessary to allow three days for the news to travel from London to Edinburgh by horse. Nowadays, of course, such a delay is entirely unnecessary, yet the tradition endures.

One can’t help but wonder if the good people of Edinburgh derive a certain sense of pride and identity from these quaint, archaic practices, even as they may seem utterly nonsensical to the outside observer.

In the end, the market cross stands as a testament to the enduring power of tradition, a reminder that some things are worth preserving, even if their original purpose has long since faded into obscurity.

Following the passing of Queen Elizabeth II in Scotland, it took three days for the news to travel from the location of her death to the church where she was laid to rest. This delay seems quite ridiculous and out of step with modern communication capabilities.

In Edinburgh, there is a site known as the “Heart of Midlothian” which was the location of a former prison and tax office that was despised by the local population. Tradition held that people would spit on the door of the building as they walked by, as a sign of disrespect for the authorities. This tradition continues today, even though the building has been demolished

As a high-ranking Presbyterian, thel Presbyterianism is the national faith of Scotland. It is our national religion. But is Presbyterianism a prestigious denomination?

England had already adopted the lion as its heraldic symbol, so the Scots naturally chose the unicorn as theirs. On the royal coat of arms, the unicorn is placed on the left side, which in heraldic tradition signifies it as the more important or dominant symbol. The lion is relegated to the right side. This arrangement reflects the historical rivalry and power dynamics between the two nations that make up the United Kingdom.

Similarly, the religious iconography and architecture of places like St Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh, a historic Presbyterian church, evoke a bygone era that may seem out of step with modern sensibilities. These traditions and symbols, while steeped in history, can appear increasingly irrelevant or even antagonistic in the present day.

The Wars of Independence began in the late 13th century, as England and Scotland fought over the governance of Scotland. This is where we fought to maintain Scotland’s independence from England. At the very beginning of these wars, the king at the time, Robert the Bruce, sent a letter to the Pope in Rome, asking him to tell the English to stop invading Scotland.

However, Hume faced opposition from the Presbyterian church, who did not approve of his atheism. He was never employed by Edinburgh University due to his lack of religious beliefs, despite being considered one of the greatest thinkers in the English language.

Hume was known for his love of pub life and socializing. There is a tradition among Edinburgh University philosophy students of jokingly running around his statue, believing it will bring them good luck on exams, as Hume was a skeptic who did not believe in superstition.

Imagine Edinburgh in the 16th and 17th centuries, a time when the city was densely packed and full of hazards. While these buildings may not impress compared to modern New York skyscrapers, back then, they were towering structures that housed both the rich and poor under one roof. The wealthy lived on the top floors, while the lower levels were occupied by the poor. This arrangement was intended to reduce crime, as robbing a neighbor was seen as bad manners in polite Edinburgh society.

However, for those determined to steal, it was easy to target the top floors where the wealth was concentrated. To deter thieves, many buildings, including those in the Old Town, were equipped with “trip steps”—one step in the staircase that was slightly off, causing anyone fleeing with stolen goods to trip and alert the residents.

Well, a high kirk is essentially a cathedral, but Presbyterians would not call it that, as the term is slightly too Catholic for their tastes. These are a very Protestant group who wanted nothing to do with the Roman Catholic Church. However, you can call St. Giles’ a cathedral, as it has served that function for 900 years, predating the Presbyterian religion by 400 years. But this version of the church was very consequential to the Scottish story. This church has shaped us into the people we are today to a very large extent.

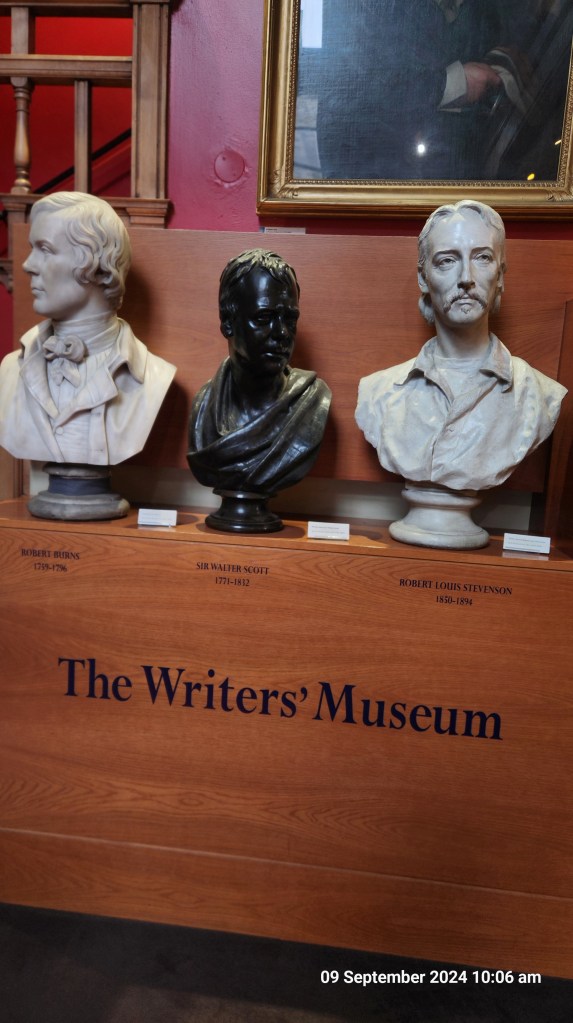

Behind us is the Writers’ Museum, once a residence, which still has a trip step. Today, it’s painted white and marked with a sign, but people still trip over it. The museum celebrates Edinburgh’s literary heritage, being the world’s first UNESCO City of Literature since 2004. The museum is dedicated to three key writers:

1. Walter Scott – Though less famous today, Scott is credited with inventing the idea of Scotland that we know today. He popularized the romantic image of Scotland with his historical novels, influencing how the world perceives the country.

2. Robert Louis Stevenson – Famous for Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The latter is often seen as an allegory for Edinburgh itself, with its dual nature of the Old Town (medieval and dark) and the New Town (modern and enlightened).

3. Robert Burns – Scotland’s national poet, Burns was a man of the people, writing in the Scots language at a time when the Enlightenment elite preferred English. Despite his fame, Burns never kept his wealth, supporting multiple families and his community instead.

Do they write on the windows?

Instead of a painted bar top, you have a poem about a barn. Okay, fair enough. As for this, poetry is five parts. I love it. It sounds like you’re saying “Burns,” but it’s spelled “Burns.” The Scottish poet we should have listened to, not born. I’ll give you that, so you can get a sense of what the Scottish language sounds like and what part Portuguese plays in it. I love that. I’m talking about a rendition of one of Burns’ poems. Burns’ poetry generally focuses on three main themes: nature, since he was a farmer and closely connected to the natural world; women, as he wrote many poems about love; and social commentary, as he often wrote about the lives of common people.

Burns often wrote about three main themes: women, nature, and drinking. He loved spending time at the pub, and his poetry reflects this. One of his famous poems, “To a Mouse,” captures his deep empathy for the natural world. In the poem, a farmer accidentally destroys a mouse’s nest while plowing his field. The farmer, representing Burns, apologizes to the mouse for the destruction. The poem is an apology from humankind to nature for the damage we cause, showing Burns’s forward-thinking view of environmental issues, long before they were widely recognized.

The line “I’m truly sorry man’s dominion has broken nature’s social union” highlights this sentiment, emphasizing that humans and animals share the same struggles in life. This is where the famous phrase “the best-laid plans of mice and men” originates, illustrating that both humans and animals face similar challenges.

Burns is celebrated every year on January 25th, known as Burns Night. It’s a time to gather with friends and family, enjoy haggis, and read Burns’s poems. Haggis, Scotland’s national dish, is made from sheep’s heart, liver, and lungs, mixed with oats and spices, then boiled in the sheep’s stomach. Despite its humble ingredients, it’s delicious and traditionally served with neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes). There’s also a vegetarian version made from kidney beans, but nothing beats the original.

—

Burns often wrote about three main themes: women, nature, and drinking. He loved spending time at the pub, and his poetry reflects this. One of his famous poems, “To a Mouse,” captures his deep empathy for the natural world. In the poem, a farmer accidentally destroys a mouse’s nest while plowing his field. The farmer, representing Burns, apologizes to the mouse for the destruction. The poem is an apology from humankind to nature for the damage we cause, showing Burns’s forward-thinking view of environmental issues, long before they were widely recognized.

The line “I’m truly sorry man’s dominion has broken nature’s social union” highlights this sentiment, emphasizing that humans and animals share the same struggles in life. This is where the famous phrase “the best-laid plans of mice and men” originates, illustrating that both humans and animals face similar challenges.

Burns is celebrated every year on January 25th, known as Burns Night. It’s a time to gather with friends and family, enjoy haggis, and read Burns’s poems. Haggis, Scotland’s national dish, is made from sheep’s heart, liver, and lungs, mixed with oats and spices, then boiled in the sheep’s stomach. Despite its humble ingredients, it’s delicious and traditionally served with neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes). There’s also a vegetarian version made from kidney beans, but nothing beats the original.

I don’t believe we should stop all building, as creativity in architecture is important. However, I don’t think we should build in the Shepherds area – that’s a separate issue.

This building in Ramsay Gardens was designed by Patrick Geddes, one of the world’s first town planners. Geddes argued that cities need to retain their character, so he saved Edinburgh’s historic Old Town from being demolished. He designed this building to be both functional and beautiful.

The building has been popular with Airbnb guests who can watch the Edinburgh Tattoo from the windows. It’s named after the Enlightenment poet Allan Ramsay.

The nearby Balmoral Hotel was built for Waverley Station, so travelers could conveniently stay there before their train journeys. The hotel’s clock is famously inaccurate, running 4 minutes fast to encourage people to hurry to the station.

On the hill above, the unfinished Greek-style monument was meant to honor soldiers from the Napoleonic Wars, but it was never completed due to lack of funding from the cheap Scottish people. However, the view from Calton Hill is still beautiful, especially at sunset.

The time ball tower, which used to drop a ball at 1pm to help ships set their clocks, is now broken. The 1 o’clock gun from the castle still fires, but the time ball no longer drops. This quirky Edinburgh tradition has fallen into disrepair.

—

Edinburgh is home to the Honors of Scotland, which include the Crown, the Sword of State, and the Sceptre. The fourth element, the Stone of Destiny, is also known as the Stone of Scone. We’ll discuss the Stone of Destiny separately, but first, let’s focus on the Crown, Sword, and Sceptre.

After the Battle of Culloden in 1746 and the introduction of the Dress Act, which banned Scottish culture, the Honors of Scotland lost their significance. They were lost and forgotten for 80 years until George IV, a fan of Sir Walter Scott, came to the throne. George IV loved the romanticized version of Scotland in Scott’s books and wanted to see it firsthand.

Edinburgh hadn’t hosted a king in nearly 200 years, so Walter Scott was tasked with organizing George IV’s visit. Scott not only organized a grand parade but also rediscovered the long-lost Honors of Scotland in Edinburgh Castle. He had them renovated and presented them to the king, reviving Scottish traditions and sparking renewed interest in Scottish culture.

George IV’s visit in 1822 marked the revival of Scottish traditions, including kilts and bagpipes. The king himself, unfamiliar with real kilts, arrived in Edinburgh wearing a mini skirt and bright pink tights, much to the amusement of the city.

The Stone of Destiny, which Scottish kings were traditionally crowned on, was stolen by Edward I of England in 1296. It remained in Westminster Abbey until 1950 when four Glasgow University students, frustrated by its absence, decided to steal it back. They broke the stone during the heist and had to hide it in Kent before returning it to Scotland. The stone was eventually repaired and returned to Scotland, becoming a symbol of Scottish pride and resilience.

The students who stole the Stone of Destiny returned it to Scotland and left it at Arbroath Abbey, covered with a Scottish flag and a note stating it belonged to the Scottish people. However, the authorities took it back to London, where it remained until 1996.

In 1996, when Scotland reopened its Parliament, the Stone was finally returned to Edinburgh. It was met by a Scottish guard and piped into Edinburgh Castle to the tune of the Mission Impossible theme. This marked the end of the Stone’s 700-year absence from Scotland.

Despite its return, controversy surrounds the Stone. Some believe the original Stone was never recovered and that the one returned was a fake. Others think the real Stone was hidden, with various claims about its whereabouts, including a pub in Glasgow that purports to have it.

In addition to the Stone’s story, Edinburgh’s Greyfriars Kirkyard has literary connections. Charles Dickens, visiting in the 19th century, allegedly misread a gravestone for Ebenezer Scroggie as Ebenezer Scrooge, inspiring the character from “A Christmas Carol.” J.K. Rowling drew on similar themes for names in the Harry Potter series.

One notable figure buried in Edinburgh is William McGonagall, Scotland’s worst poet, known for his dreadful poetry despite his passion. Here’s a snippet from one of his better works:

“Over yonder on a hill,

There was a cow, but now it’s still.”

William McGonagall, Scotland’s infamous poet, faced rejection wherever he went. In Edinburgh, people ignored his poetry, and in New York City, he was met with similar indifference. Despite this, McGonagall returned to Edinburgh and embarked on a grueling 150-mile walk to Balmoral Castle, hoping to gain recognition from Queen Victoria. Instead, he was beaten and sent away.

McGonagall’s ambition was unshaken. Today, he is celebrated for his dreadful poetry, which is now appreciated for its humor. His books sell well, not for their quality, but because they’re amusingly bad. McGonagall’s story is a testament to pursuing one’s dreams despite setbacks. His persistence turned him into an unlikely hero and a role model for anyone with aspirations.

Whether you want to be a poet, a musician, or anything else, take McGonagall’s example to heart: follow your passion, no matter what others say. Success might come in ways you never expected, even if it’s only after you’re gone

.

Edinburgh’s Unique History and Geography

Edinburgh’s landscape has significantly shaped its development. The city is built around the remnants of an ancient volcano, with Edinburgh Castle sitting atop its basalt plug. The Ice Age glaciers carved out the land, forming what is now the Royal Mile, a ridge that slopes from the Castle down to Holyrood. The geography provided natural defenses, which helped Edinburgh grow and remain centralized for over 3,000 years.

In 1513, Scotland launched an ill-fated invasion of England, which ended disastrously for the Scots. The Scottish King, James IV, was killed, and his body was sent to London as proof of Scotland’s defeat. Fearing a counter-invasion, the Scots built the Flodden Wall around Edinburgh, which confined the city for 200 years. During this time, the population was packed within the walls, leading to the construction of some of the tallest buildings in Europe at the time.

The city’s lack of plumbing, combined with overcrowding, turned Edinburgh into a notoriously filthy place. Waste was collected in buckets and thrown out of windows onto the streets below. To manage this, a law was introduced requiring waste to be thrown out only after 10 PM, leading to a nightly flood of sewage on the streets. This timing coincided with pub closing hours, meaning the only people on the streets were often drunk, giving rise to the phrase “shit-faced.”

This mix of history and mythology is part of what makes Scotland unique. Whether or not all these tales are entirely true, they reflect the spirit of Edinburgh—a place where reality and legend often intertwine

These windows overlook the streets leading down to what is now a garden, but in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was the Nor Loch, also known as the North Lake. It wasn’t a lake but a filthy body of water filled with the city’s sewage, dead bodies, and disease. This polluted water served as a natural defense on Edinburgh’s north side.

The Old Town was overcrowded, with buildings frequently collapsing, making it one of the most dangerous and unsanitary places on Earth. To escape these conditions, Edinburgh’s wealthy residents moved to the New Town in the 18th century, leaving the poor behind in the Old Town’s poverty and decay.

This created a lasting divide in Edinburgh’s character—a city of duality. The Old Town represents the medieval past, while the New Town embodies the Georgian era. This division is still evident today, symbolizing the contrast between Scotland and Britain, and between the old and the new.

During the Enlightenment, Edinburgh not only transformed itself but also led the world into the modern age—a remarkable achievement for Scotland.

Scotland’s religious and political landscape changed significantly after King James VI of Scotland became King of England in 1603. The Scottish aristocracy and political class moved to London, leaving a void in Edinburgh. This allowed academics and freethinkers like David Hume to flourish, as there was no authority to tell them what to think.

The Greek temple in Scotland is an interesting historical site. It was originally the Scottish Parliament building, constructed in 1630 and used until the Act of Union in 1707 when governance of Scotland moved to Westminster in London. Prior to being the Parliament, this area was the graveyard for Edinburgh. When the building was constructed, most of the graves were exhumed and relocated, except for one person who remains buried under parking space #23. While the Greek-style architecture may seem out of place in Scotland, it reflects the country’s rich cultural heritage that extends beyond just English or Scottish traditions. This building serves as a unique example of Scotland’s history and identity.

John Knox was the foremost leader of the Scottish Reformation and the founder of Scottish Presbyterianism. As a Presbyterian, Knox believed in the authority of the Bible and the direct relationship between individuals and God, without the need for intermediaries like the Pope or a king.

Knox was influenced by the teachings of Protestant reformer George Wishart, and after Wishart’s execution, Knox became a prominent preacher of the Reformation in Scotland. He helped establish the constitution and liturgy of the Reformed Church of Scotland.

Knox’s theology emphasized the importance of education, and he was a driving force behind efforts to educate the Scottish people.

The Presbyterians believed that the Scots are God’s chosen people – a notion that often elicits confusion and amusement, as we may not instantly appear recognisable as God’s chosen. There is certainly a lot of drinking and swearing going on, but we do consider ourselves God’s elect. This idea goes back to the period in Scotland known as the Wars of Independence. These wars rumbled on for around 400 years, with no definitive start or end.

This letter claimed that the Scots are a much more ancient people than the English, and that we had been running our own country for thousands of years before the English even became a people, and that we did not need them coming up here and ruling our country for us. This letter is very famous in Scotland, known as the Declaration of Arbroath. It is a focal point for Scottish independence, as the Declaration claims that as long as there are 100 Scots alive, we would never, under any condition, come under the rule of the English. It states that it is not for money, power or glory that the Scots fight, but for freedom alone.

—Learn more:

1. [English Civil Wars | Causes, Summary, Facts, Battles, & Significance | Britannica](https://www.britannica.com/event/English-Civil-Wars)2. [English Presbyterianism, 1590-1640 by Polly Ha (Ebook) – Read free for 30 days](https://www.everand.com/book/348516493/English-Presbyterianism-1590-1640)3. [English Presbyterianism, 1590-1640 – Polly Ha…](https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=12258)

The Presbyterian practices are similar to Roman Catholic practices, with some differences. The main difference is in the handling of the communion elements – the Presbyterians do not consume the head, just the bread and wine.

There is a Presbyterian general assembly that meets annually, where the church president discusses larger theological and practical matters. The Presbyterian church in Northern Ireland has a complex history, as it was used by the Scottish king James VI to help subdue the local Catholic population through the Plantation of Ulster.

The Presbyterians sent to Northern Ireland were specifically chosen for their ideological opposition to Catholicism, to ensure they would not assimilate with the local population. This is a major factor in the ongoing sectarian tensions and “Troubles” in Northern Ireland.